Wonder Woman: superhero film or morality play?

Recently, my daughter and I saw the new theatrical feature film, Wonder Woman. Superhero films have been abundant in recent years, and I have found most of them to be hit-or-miss. Early reviews for the film were favorable, but even so my expectations were guarded. I was pleasantly surprised. The film was quite good, with some unexpected and original takes on the iconic character, her origins, and the world she entered.

Before I continue, this article is filled with spoilers. I can’t say what I want to say without giving away key points of the film. So if you plan to see the film and hate spoilers, then stop here.

You have been warned.

I would say that this film was a morality tale, or at least a fairy tale with very strong moral messages, masquerading as a superhero story.

This film took the well known character of Wonder Woman and re-imagined her in a very different way. For starters, the time frame of her base story was pushed back almost 25 years. In this interpretation of the character, it is World War I that provides the backdrop, as opposed to World War II. The world of 1918 was far removed from the world of 1941.

The original comic book character of Wonder Woman was created during World War II, and that conflict was an integral part of her stories. Diana’s primary adversaries were Nazi sympathizers, Japanese spies, saboteurs, corrupt war profiteers, and meta-humans created by the Axis to counter the likes of Batman, Superman, and herself. It was pretty standard comic book fare, and there was little or no ambiguity between who were the good guys and who were the bad guys.

But that formula wouldn’t have worked as well with World War I. World War II was the worst kind of war: it had to be fought. Civilization itself was being threatened by a very frightening social belief system that was being encouraged and fueled by the ravings of a madman. The line between good and evil was very clear, and just about everyone knew what was at stake.

World War I was a different story from a different time. World War I, or the “Great War,” was largely driven by a sociopolitical cycle that had dominated world politics since the end of the Roman Empire. Specifically, the “Balance of Power.” It was believed that every one or two generations, a major war was necessary for maintaining world order. If any one country or coalition of countries became too powerful, the long term results for civilization as a whole could be disastrous. As a matter of due course, every twenty to thirty years the nations of the world (especially in Europe) would squabble among themselves. When things died down, the various military arsenals of the world would be greatly depleted, political alliances would be re-drawn, maps would change, regimes would rise and fall, then everything would continue as usual. And here’s the funny part: throughout history no one seriously expected these periodic wars to solve anything long term. It was always assumed that after a country gets punched in the nose, over the next three decades it would rebuild it’s arsenal, then come back for a rematch. And sometimes that nation would win the rematch. That was part of the whole point. Wars made sure that no one nation became too powerful, or remained at the top for too long, or that the ambitions of one nation began to dominate the fate of many others.

War was analogous to periodically releasing steam from a pressure engine. If it wasn’t done, then eventually the pressure would cause the engine to explode, and civilization as a whole would suffer. Up until the early twentieth century, some historians cited the catastrophic collapse of the Western Roman Empire as an example of what can happen when the “Balance of Power” is not effectively maintained.[1]

By the time of the Napoleonic Wars this belief was being called into question. Or, at the very least, the belief that war as a means of maintaining the Balance of Power was being questioned. During the Napoleonic Wars, people were looking at the devastation of war and started to wonder if there was another way to handle the Balance of Power equation, because periodic wars were proving to be just as destructive as the cataclysmic fall of civilization that they were supposed to prevent.

After Napoleon finally went into exile, the major nations of Europe concluded that in the future, political problems should be solved by dialogue. There was no formal committee for this, only a general consensus that diplomacy should be used instead of force. Sadly, it didn’t take hold. And some of the diplomats of the era proved to be just as dangerous as any warlord. It has been argued that many of the nineteenth century “diplomats,” Klemens Von Metternich in particular, were far worse than any warlord.

The issue was visited again after the Franco-Prussian War, but again, little changed. The Boer Wars and the Spanish-American War demonstrated, decisively, that military technology had moved beyond most military thinking.

By 1910, enough people had picked up the growing pattern and were determined to put a stop to it, and wanted to settle the Balance of Power equation differently. However, diplomacy had proven to be a partial success at best. The general belief was that another major war was inevitable, and that ultimately nothing could prevent it. Political and social tensions were simply too high, and more importantly, too many people were itching for a fight.

Some suggested that it would be better to have this major war sooner than later, given that military technology kept getting deadlier and deadlier. Furthermore, perhaps we (humanity) should take this “opportunity” to settle some old issues that have been festering for decades or centuries. As a species, we needed to have one final, massive, spectacular slam bang of a war that will settle the world’s problems once and for all: a war to end all wars.

I just grossly over-simplified things, but stay with me.[2]

It was into this prevailing global mindset, the belief that war was an effective way to maintain world order, that Diana was thrust.

Again I must say that if you haven’t seen the movie and want to avoid spoilers, then for the love of Zeus, stop reading now!

Diana’s home, Paradise Island, was hidden from the rest of the world by what can only by called a strange weather pattern. This small, lush island was the last stronghold of the Amazon warriors of the ancient world. Diana grew up believing that Hippolyta, Queen of the Amazons, had crafted her from clay, and that she was intended for some great purpose, but that purpose had not yet revealed itself.

Diana’s world was upset when a German airplane stumbled into the strange weather pattern, and crash landed off the shore of Paradise Island. Inside the plane was Steven Trevor, an American spy. He was carrying vital information about German chemical weapons, and was en route to British intelligence in London when the Germans shot him down. Diana found Steve to be fascinating. One, because he was a man, and those are scarce in Amazon country. And two, because he came from the world outside. Everything he said about the world outside ran against what she thought she knew to be the truth.

The Amazons had set up shop on this remote island, where they would wait until Ares, the ancient Greek god of war, re-appeared. For almost 2000 years these women were waiting for a sign that Ares was out and about, but they never heard a thing. So, the Amazons assumed humanity was totally at peace.

But along comes Captain Trevor and his stories about the “war to end all wars,” and some of his stories were horrible. Several of the Amazons were confused. There have been several wars? How long has Ares been running amok? And why didn’t anyone inform us? Trevor explained that higher powers, like Ares, had nothing to do with it, because humanity was perfectly capable of committing evil without such help. The Amazons could not wrap their heads around this (well, most of them couldn’t). Diana, like most of her comrades, remained convinced that Ares was involved, and that Steve Trevor’s perception was being clouded somehow. Things went back and forth for a while, but ultimately Diana leaves with Steve Trevor for the world outside, determined to find out just what was going on. And if possible, destroy Ares.

She experienced a serious case of culture shock when confronted by the world of 1918. Political manipulation, economic inequality, deceit, and a whole lot of sexism left her flabbergasted. But she handled it surprisingly well, and remained determined to find Ares, take him out, and put everything right. Along the way she did some serious ass kicking.

Diana was portrayed as a very effective warrior, especially in hand to hand combat.[3] But at the same time, she was unbelievably naive. She had spent her life living in a utopia, cut off from the rest of the world in just about every way. She had grown up believing that humanity had been created by Zeus and the other ancient gods in their image, and that they were put on earth to live prosperous lives and do great things. She saw humanity as a perfect creation. In her mind, the only way humanity could be behaving imperfectly was if another god, such as Ares, was exercising some unnatural influence over them. Steve, and some of his comrades, tried to explain to her that other possibilities existed, and that things were not as simple as she assumed. But she steadfastly paid no attention to that.

For most of the film she was driven by a determination to find and kill Ares, confident in her belief that doing so would solve all problems. Eventually she finds the man she believes to be Ares in a German chemical weapons depot, and after a brief but intense fight, executes him. Believing that she had completed her mission, she went to the top of a signal tower to greet the sun in triumph. She is horrified to see the troops of the German army continue to carry out their duties, and hear the rumble of artillery in the distance. She couldn’t understand why humans were still waging war!

Shortly after this, Steve finally gets her to except the notion that humanity is not, and never was a perfect creation. She is still struggling with this realization when she finally meets the man who actually is Ares. Ares calmly explains to her that indeed, Zeus and the other gods created humanity in their image, with the aim of doing great things. But in order to create creatures capable of great things, they had to be given free will. That in turn gave them the ability to make “evil” decisions. Many humans have done exactly that, throughout history, and Ares had very little to do with it.

Ares goes on to state that it was actually humanity’s abandonment of their higher purpose that compelled him to start interfering in the first place. He was very disappointed, even distraught, at how humanity had fallen so far astray, and ultimately concluded that the only rational choice left was to destroy them all and start anew! Ares viewed wiping out the human race as something akin to a mercy killing! In horror, Diana realizes that Steve was right: humanity is flawed, and does not need the influence of a higher power to perform acts of evil.

But at the same time, Diana was also at least partially right: Ares had been influencing humanity. Ares himself said that throughout history he would periodically give certain individuals a nudge in a certain directions, usually to start or prolong wars. This was all done with the aim of ultimately destroying humanity. Even so, Ares was quick to say that he never explicitly told or compelled any humans to carry out evil acts. He simply told them that they had the option. The fact that humans went through with the actions was their decision, and theirs alone. Ares considered himself blameless.

Diana didn’t agree, and chose to have nothing to do with his sick plan, despite the tempting offer Ares gave her. As expected, they started to fight. But for a brief moment she looked ready to fold up and sulk her way home to Paradise Island. Both Ares and Hippolyta had told Diana that “humanity doesn’t deserve you,” and now that she could see just how imperfect humans could be, she understood what they meant.

But there was another card in play, and his name was Steve Trevor.

The finale of the film takes place on a German military base, in occupied Belgium. From this base a bomber, laden with an exceptionally messy chemical weapon, was going to launch an attack on London. Such an act would have derailed any peace talks (this was October of 1918, when things were winding down), and Great Britain would have plunged into chaos. A continuation of the war was exactly what Ares wanted, so he made sure the bomber took off as planned, despite what was going on around him. But in the confusion, Steve Trevor had boarded the plane during take off. Shortly before boarding the plane, during a lull in her fight with Ares, Steve told Diana that he was going to destroy that plane no matter what, even though it would almost certainly result in his death. His parting words to her were a confession of love:

“I can save today, but you can save tomorrow. Diana, I love you.”[4]

I got the impression that Diana had never experienced love in the way Steve was referring to it. That is to say, the wonderful combination of philia, storge, agape, and eros that exist between two people who are in love. It is understandable that Diana would be new to this, since such relationships generally aren’t part of Amazon society. Also, at an earlier point in the film, there is a strong implication that Diana and Steve became physically intimate. We don’t actually see this, but the film uses some long established tropes to suggest events that what would otherwise get a love scene. It isn’t definite that they made love, but I think it’s safe to assume that they did or at least came close. Unlike most theatrical sequences of this type, it isn’t gratuitous. It is actually rather important to the story!

Diana is lamenting the wretched state of humanity, when she sees the bomber explode in the distance. She knows that Steve has sacrificed his life, but by preventing the chemical weapon from being dropped on London, countless lives were saved. Steve’s act of self-sacrifice showed Diana that sometimes humans do live up to the ideal that the gods originally intended, and that while they are capable of great evil, they are also capable of great good. Fueled by this knowledge, she charges at Ares for another round.

The resulting final battle between Wonder Woman and Ares was everything that movie audiences expect: a huge slam bang that created millions of dollars of adjusted property damage, spectacular visual effects that made everyone in the theater jump, and a dramatic musical score that would give Richard Wagner performance anxiety.

I found myself cheering Diana on when she went after Ares in a burst of righteous anger. You go, girl! But as thrilling as that fight was, for me, it was the dialogue that led up to it that made this film so good, and why I believe it to be a morality play.

In the denouement scene, we see that Diana has been living among humans since 1918, presumably under various secret identities. Today she lives in Paris, working as a historian at the Louvre. In her closing soliloquy, she admits her knowledge of humanity’s flaws, and that evil is, and always has been, part of the human condition. People like Ares will always work to exploit that. But she also knows that humanity can do great things, and it’s up to people like herself to make sure that good people prevail. Her final words sum things up pretty well:

“I used to want to save the world. To end war and bring peace to mankind. But then, I glimpsed the darkness that lives within their light. I learned that inside every one of them, there will always be both. The choice each must make for themselves – something no hero will ever defeat. And now I know… that only love can truly save the world. So I stay, and I fight. I fight for those who cannot fight for themselves. And I give, for the world I know can be. This is my mission, now and forever.”[4]

Chills!

In many ways, I found the story to be a parallel telling of the Judaeo-Christian parable about free will. Throughout the ages, philosophers and theologians have asked why God permits evil in the world, why He permits humans to do evil things, or why He allows bad things to happen to good people (poor Job). Augustine’s answer is that evil was created by humanity, not God. The thing is, in order for God to “create man is his own image,” it was necessary for Him to give humans free will. But with free will comes the ability to choose evil. It was an inherent risk that God took, and He hoped that his creation would choose not to pursue it. But as we know from the creation myth, a few nudges from the Devil at a few key moments gave humanity the urge to explore what should be left alone, and things went downhill pretty quickly. But, the Devil, just like Ares, had an out:

“I didn’t tell Adam and Eve to eat those apples, I only pointed out that they could, and what the possible benefits were. The decision to actually take a bite was theirs, and theirs alone.”

In the New Testament we get the famous counter-example. During the trials in the desert, the Devil tries to tempt Christ with worldly delights. By pointing out that someone with his natural charisma and influence could effect and control millions of people, Christ could quickly rise up in the world and rule over it. But Christ wanted humanity to retain it’s free will and ability to choose, and he wasn’t interested in political power. So, He respectfully declined.

Diana did the same with Ares, and for much the same reason. Granted, the Devil’s disappointment was surprisingly muted when compared to that of Ares. But the Greek gods tended to be a hot-tempered lot, so Ares’ tantrum was a bit of a given.

I greatly enjoyed the film. I enjoyed it far more than I expected to, and I would be more than willing to see it again. But, there are two things I really would have liked to have seen. My tongue is now firmly in my cheek, by the way.

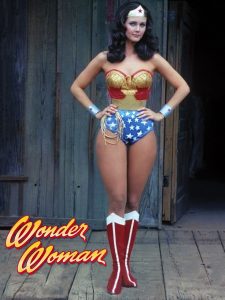

- First, a cameo by Lynda Carter. She was the definitive Wonder Woman for a generation, and could have easily been included in one of the crowd scenes. I suspect she either wasn’t available, or wasn’t interested. It could be that she didn’t want to upstage Gal Gadot with a bit of stunt casting.

- Second, the pirouette-explosion costume change. The television show turned that into a running routine, and as a kid I loved watching it. It has also been featured in the printed comic books, and I understand that some animated portrayals of Wonder Woman have used it. I think it would have looked great on a big screen. But seriously, I’m not sure where it could have been included. Perhaps the sequence when Diana changes out of the party gown while riding through the forest could have accommodated the iconic spin. However, the spin-boom-transform sequence is inherently campy, and might have distracted from the otherwise muted presentation of events at that point in the film.

Since both of those things fall into the “fan service” category, they would have been fun to see, but hardly necessary. It’s also possible that they could happen in a future film, such as Justice League. However, this film didn’t have much “fan service” at all. It didn’t need it. And that made it that much better.

- This is actually rather funny, because constant warfare was one of the key causes for the Roman Empire’s collapse. It had become too week and too strapped for resources to maintain itself. I don’t know why historians of the early twentieth century often leave that out.

- I am compelled to point out that many Americans don’t really appreciate the impact of World War I; even fewer can understand the motivations behind it. Personally, I think World War I was one of the most foolish things humanity has ever done. One would think that after the various wars of the 1800’s, the major nations of the world (particularly in Europe) would have learned that the Balance of Power concept wasn’t just about military might. It also included economic and social aspects, and that war was no longer an effective short term solution. Some historians have suggested that between the American Civil War and the Spanish-American War, the United States had already learned that particular lesson. That could be why so many Americans “don’t get” World War I. It may also be one of the reasons why we acquired such a bad reputation while “over there.”

- During the course of the film she learns how to use a rifle, and does pretty well with it. But she doesn’t consider it honorable to fight from such a long distance, and prefers to use a sword and shield.

- I lifted this text from IMDB. I don’t think the transcription is 100% accurate, but I do remember that these words, and certainly these sentiments, were relayed in dialogue.

.jpg)