This is a story my brother likes to relay on Veteran’s Day.

Our maternal grandfather, Joseph Habecker, at the age of 18, was drafted into the United States army in Lawrence, Massachusetts.

As he headed to the draft board on the assigned day, he saw his friends running back from the board excited and shouting “The war is over!” My grandfather and his friends threw their draft cards into the Merrimack River.

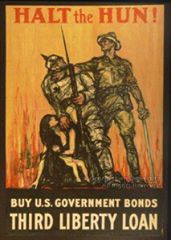

Meanwhile, across the Atlantic, the Germans had just surrendered to the Allies. An armistice was arranged such that all hostilities would cease on the 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month in 1918. Why all the elevens? So no one would forget the sacrifices of the last war we would ever have.

Sadly, other wars came, and Armistice Day became Veterans Day.

This leads me to stories of some other Veterans from another era. Our maternal grandmother (“Memere”) had one sister and nine brothers, three of which saw combat during World War II.

Leo Langlais served with the US Marines during the “island hopping” campaign in the Pacific theater. He even fought at the battle of Guadalcanal. As some point he contracted malaria, and was moved to a medical facility away from the front lines. When he was strong enough to return to duty, the military sent him to the machine shops that worked on the tanks and jeeps used by the ground troops. There he worked as a machinist until VJ Day. As he once put it, “they took away my rifle and gave me a tool box.” He died in the early 1980’s at his home in Salem, New Hampshire.

Donald Langlais served in the US Navy, first on destroyers and then on a submarine, both in the Pacific theater. According to family legend, he had two ships shot out from under him, and witnessed the destruction of at least a dozen others (both American and Japanese). I know very little about Donald, as he died before I was born. From what I’ve been told, he had what is sometimes called “a bad war,” and he never fully recovered from the experiences he had. The nightmares and visions plagued him until the very end. Today, we call this Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. Back then it was called “shell shock” or “battle fatigue,” but it’s the same thing, and it’s a very real and debilitating condition. Donald died in the late 1950’s, if I recall correctly.

Roland Langlais was with the US Army, and unlike his brothers, was in the European theater. He served under General Patton, as a mechanic and heavy equipment operator with the Red Ball Express. The Red Ball convoy moved tons of supplies from bases in Normandy to the front lines of the Allied invasion forces, as they slowly but surely crept toward Berlin. Roland himself, if I remember correctly, initially worked with the heavy equipment that helped build and maintain the highways through the French countryside. Later, when the truck convoys were replaced with railroads, he was among those who maintained and repaired the rail lines and equipment. Roland died at his home in Tilton, New Hampshire, in the 1990’s.

I’m probably off with many of the specifics, but I do know that all three of them served with distinction – each of them came home with a Purple Heart – and they were all proud to have served their country in it’s time of need.

At 11:11am, on November 11, please stop what you’re doing and pause to remember all the veterans of all the wars. Those who, like the Langlais brothers, served with distinction, and gave the full measure so that people like Joseph Habecker wouldn’t have to.

I recently remembered something our mother used to say about her mom, who I always knew as Memere. That’s a French-Canadian term of endearment that idiomatically means “grandmother.”

During her childhood, my mom’s family was one of the few in her neighborhood that had a telephone. I remember Memere having a ‘telephone desk,’ with a small chair and writing table. Mom said that throughout the war years, whenever the phone rang, Memere would take a deep breath and sit down at the little desk before picking up the receiver. Since she had three brothers in the military, and was the designated point of contact for her extended family, Memere always dreaded that the call would be one of “those calls.”

Mom said that the day news of Japan’s surrender arrived, was one of the few times she ever saw her mother cry, and these were tears of joy and relief. The phone hadn’t rung for several weeks. That meant all three of Memere’s brothers had survived World War II.